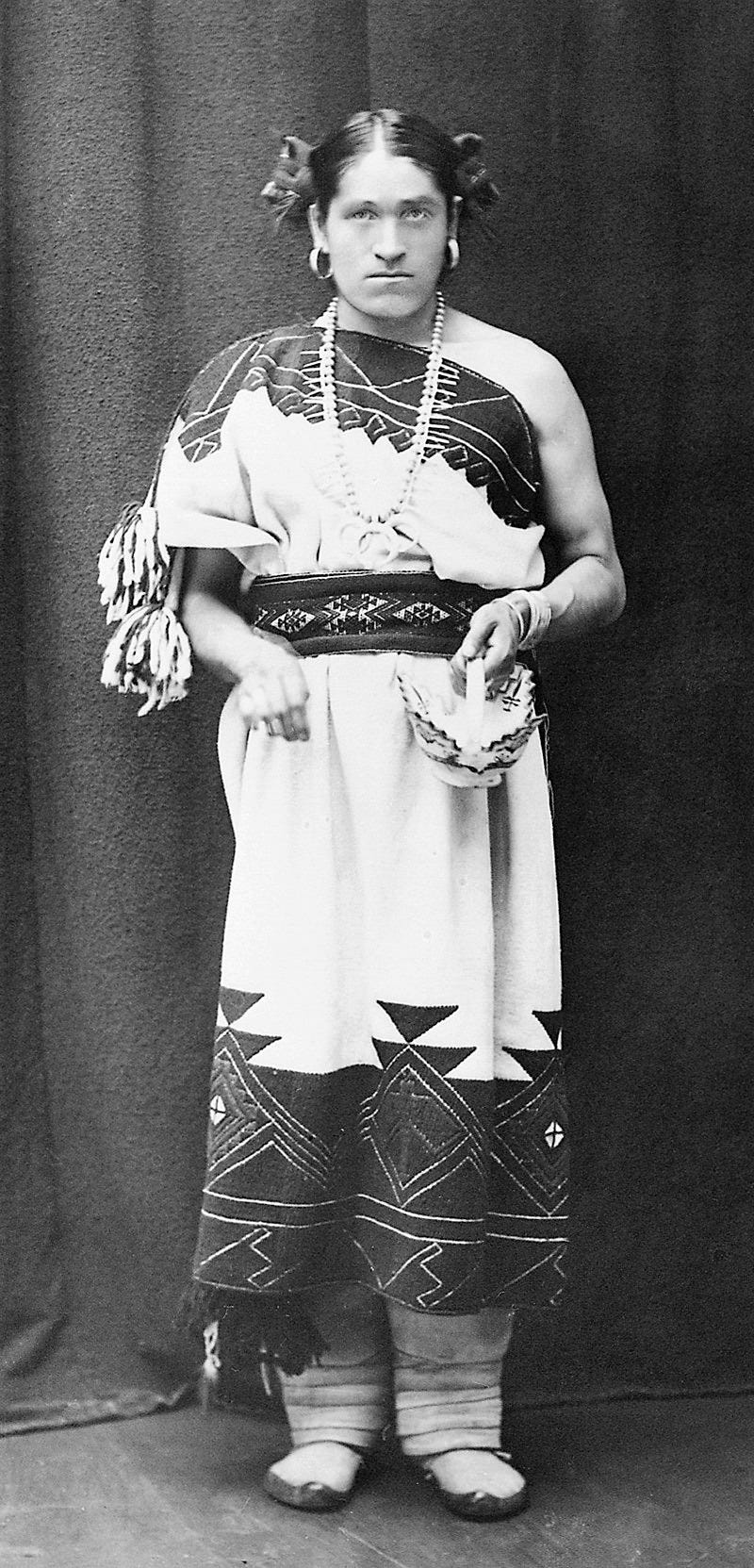

The story of We'Wha, the Two-Spirited ambassador of the Zuni tribe

Assigned male at birth in 1849, We'Wha was an important cultural ambassador in early American society

In our continuing series on trans and non-binary people through history, we look at We’wha, who became a famous cultural ambassador for Native Americans in the 1800’s and even met with President Grover Cleveland.

We’wha, a member of the Zuni tribe who were located in today’s New Mexico, was born in 1849 and recognized several years later as a lhamana (Two-spirit) by their community. At the time the Zuni peoples were still allowed to practice their cultures and traditions, and the recognition of two-spirited individuals was a part of their culture, as gender fluidity was recognized in other Indigenous cultures around the world.

Two-spirit (also two spirit, 2S or, occasionally, twospirited) is a modern, pan-Indian, umbrella term used by some Indigenous North Americans to describe Native people in their communities who fulfill a traditional third-gender (or other gender-variant) ceremonial and social role in their cultures.

As a lhamana in the Zuni tribe, We’wha learned traditional women’s roles such as grinding and making corn meal, making ceremonial pottery, cooking, and various domestic tasks, as well as later working on a Zuni farm in more traditional male roles.

We’wha also studied crafts. Taught by a kinswoman who was an expert in ceramics, We’wha trained for years to master the elements of the pottery, many of which held ceremonial importance. We’wha became a skilled weaver (usually a male role), learning different looms in order to make blankets, belts, and sashes. We’wha became known for their talent as a craftsperson, during a period (approximately 1848-1880) in which Pueblo textiles, particularly those in the distinctive Zuni style, flourished. We’wha was among the first Zuni to sell their pottery and textiles, helping to bolster Indigenous arts more widely.

At the same time, We’wha was also a member of the men’s kachina society, which performed ritual masked dances. We’wha also joined the medicine society known as beshatsilo:kwe (Bedbug People) after a shaman cured them of an ailment. Membership in these societies enabled We’wha to further their knowledge of Zuni lore and ceremonies. We’wha mastered the demanding memorization as well as the improvisational skills necessary to impart the tribal tales and stories that were part of Zuni rituals.

In 1879 while working for Protestant missionaries by caring for their young daughters, We’wha met an anthropologist named Matilda Coxe Stevenson whose husband was leading an expedition to collect artifacts and record the customs of the Zuni people for the newly formed Bureau of Ethnology. Mrs. Stevenson was immediately impressed by We’wha’s extensive cultural knowledge of the Zuni people and often referred to We’wha as “the most intelligent person in the Pueblo.”

We’wha was able to learn English through this friendship, and in 1885 they traveled to Washington DC as part of a cultural ambassadorship mission by the Stevensons who wanted to promote interest in further anthropological study of the Indigenous peoples. We’wha became a sensation in Washington and they presented President Grover Cleveland and his new wife a hand-crafted wedding gift. Newspapers covered We’wha’s activities closely, reporting with great interest on the “Indian princess” as Washingtonians believed them to be assigned female at birth.

We’wha went on to assist the Stevensons with ethnographic research for the Smithsonian National Museum by explaining the significance of Zuni artifacts, posing for photographs to document Zuni weaving, and donating crafts to the museum’s collections. They were also commissioned to create Zuni ceremonial pottery for the National Museum in Washington DC as they were a very accomplished potter, and followed the strict religious protocols that went with making Zuni pottery. As a talented weaver, We'wha also created baskets, dresses, blankets, and sashes. It was said that We'wha had an eye for likable patterns and colors. George Wharton James, an expert on Native American weaving styles wrote, "She was an expert weaver, and her pole of soft stuff was laden with the work of her loom-blankets and dresses exquisitely woven, and with a delicate perception of colour-values that delighted the eye of the connoisseur".

Unfortunately despite We’wha’s work as an ambassador for the Zuni people, the US Office of Indian Affairs decided the Zuni and other Pueblo tribes were to be assimilated and their cultures dismantled as they were absorbed into Western society, causing the loss of recognition of the lhamana and their role in Zuni society.

We’wha passed in 1896 at the age of 49, their young age considered to be a calamity amongst the Zuni. They left behind a profound legacy as a ceremonial leader, cultural ambassador, and artist who worked to preserve the Zuni way of life.